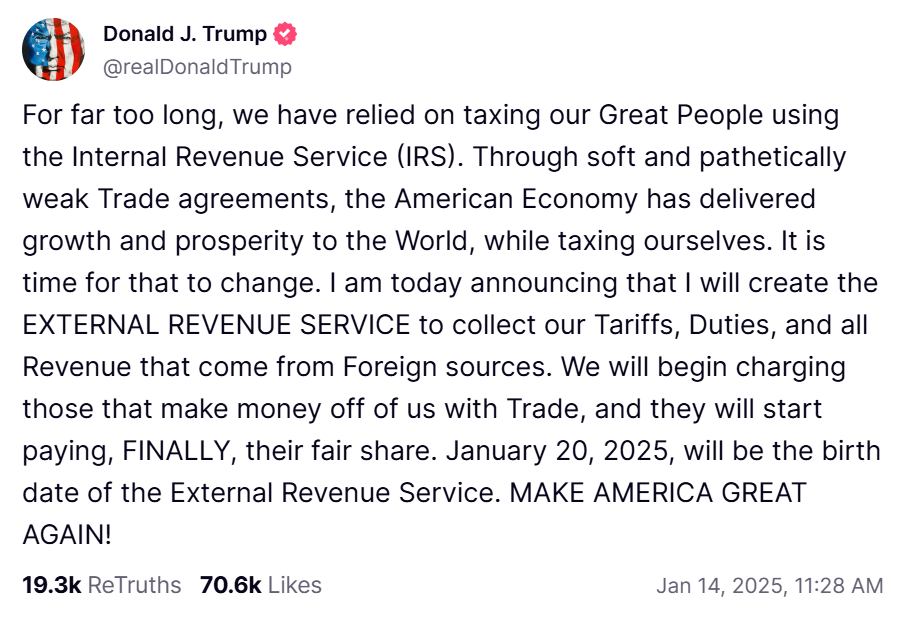

President-elect Donald Trump has floated the idea of creating an External Revenue Service, which he claims will be used to “collect our Tariffs, Duties, and all Revenue that come from Foreign sources” (sic). While we might applaud his rhetorical flair, his choice of words belies a fundamental misunderstanding of how tariffs actually work.

Before we begin, we should address the elephant in the room: we already have an agency that does this: US Customs and Border Protection. Created as the US Customs Service in 1789 and breathed into existence by none other than George Washington himself, the agency was transferred and rebranded to its current form in 2003 with the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. Changing the branding of an already-existing entity — or even worse, duplicating the work of another agency — does nothing to facilitate government efficiency.

But more to the point, the verbiage used in his post on Truth Social reveals that Mr. Trump is confused on the concept of the incidence of taxes. Simply put, when economists refer to the incidence of a tax, we are referring to the share of a tax that is paid by consumers and the share paid by producers.

Suppose we have a simple candy bar, sold for $2 at a gas station. Fortunately, this gas station is in Montana, where there is no state sales tax. You go to the attendant with a candy bar that has a sticker price of $2, hand them two crisp one-dollar bills, and you can be on your way. But now, let’s pretend that Montana enacts a state sales tax of $1 per unit. How much will the $2 candy bar cost now?

One might be inclined to believe that the price will be $3 because, after all, the candy bar originally cost $2, we’re adding a $1 tax, and, as my five-year-old son reminds me, 2+1=3. But as we learn in Econ 101, while my son is correct in math, he is (as of yet) untrained in economics (I’m working on it).

Since demand curves slope down and supply curves slope up, both the consumer and the producer will end up paying some portion of this $1 tax. It could be the case that the price the consumer ends up paying after this tax only rises to $2.50. The seller, however, would only get to keep $1.50 for the sale of the candy bar. And since $2.50 – $1.50 = $1.00, we’ve found our $1 per unit tax. In this example, the consumer pays half of the tax in the form of higher price paid and the seller pays the other half of the tax in the form of lower revenue kept. The incidence of the tax felt by consumer and seller is 50 cents each. It could also be the case that the incidence of the tax is only 25 cents for consumers and 75 cents for seller, in which case the consumer would pay $2.25 and the seller would keep $1.25 per candy bar sold. Again, the difference between the price paid by consumers and the price received by sellers is always going to be the amount of the tax: one dollar.

Determining the exact share of the tax burden is, to me, a fun exercise and is actually what first intrigued me about economics when I was in college. I fully understand, of course, that on this dimension (and clearly only this dimension), I am strange.

The above represents the economic incidence of a tax. But there is also what we call the legal incidence of a tax. The legal incidence of a tax refers to whom must actually send the tax money to the government. With candy bars, we typically assign the legal incidence to the gas station, i.e. the seller. This is primarily done for accounting reasons: stores keep detailed records of every sale they make. Auditing them to see how many dollars’ worth of sales they had each year is a relatively simple exercise, because they already have those records. By contrast, auditing each and every consumer for each and every purchase they’ve made would be onerous to say the least. So even though the gas station, legally, “pays” the tax in the sense that they are the ones who actually send the government the full dollar of tax money, the reality is that both consumers and sellers pay a portion of the tax. Whether the legal incidence is placed on the consumers or the producers makes no difference for the economic incidence whatsoever.

Despite what some have claimed, tariffs are taxes and as such they operate in the exact same manner. The only difference between a tariff and a traditional sales tax is the location of the seller. A sales tax is imposed on a seller within the US, and a tariff imposed on a seller located outside the US.

Other than the location of the seller, the two taxes work exactly the same. If a company in China is currently selling, for example, tires to consumers in the US, what will happen if the US decides to impose a tariff on these Chinese-made? The price of tires will continue to rise as long as the tariff remains in place. Importantly, the consumer price of the tires will likely not rise by the full amount of the tariff reflecting the idea that the Chinese tire manufacturers will “pay” some of the tariff in the form of lower retained revenue from each sale.

More likely, the Chinese tire manufacturers will announce the number of dollars that they will get to keep as the “price” of the tires and then will add the tariff “at the register.” This is exactly the same behavior that we see at stores throughout the US in localities with a sales tax: the sticker price says one number but we all understand that, at the register, the store will add the tax to that number.

The above might seem too simplistic. There’s no way that this actually happened, right? Funnily enough, this is exactly what happened. In 2009, the Obama Administration imposed a tariff on “new pneumatic tires, of rubber, from China, of a kind used on motor cars (except racing cars) and on-the-highway light trucks, vans, and sport utility vehicles.” This tariff would be “imposed for a period of 3 years” and would start at 35 percent in the first year, drop to 30 percent in the second, and drop again to 25 percent in the third before being phased out or “sunset.”

What happened to the price of tires in the US, you ask?

They rose from 2009 — 2012 before starting to fall back down in 2013, after the tariff ended. More to the point, the price of tires never rose the full 35 percent, 30 percent, or even 25 percent. In fact, from 2009 to 2012, the price of tires “only” rose 21.7 percent. Where did the remaining tariff revenue come from? From the Chinese manufacturing companies accepting lower prices per unit than they previously had.

Importantly, though, all of the money used to pay these tariffs came from the American consumers, not China. Yes, Chinese tire manufacturers received fewer dollars per tire than they did previously and, in that sense, “paid” some of the tariff in the form of lower price per tire. But the American consumer paid a higher price for tires, whether they were Chinese- or American-made, and in that sense paid some of the tariff in the form of higher prices.

With this new agency being floated, President-Elect Trump would have us believe that he is going to force foreign companies to “[pay], FINALLY, their fair share” (sic). The challenge here will be one of jurisdiction. The United States does not have jurisdiction in other countries (though US leaders sometimes forget this). We cannot legally force companies in other countries to do anything.

Even if the US could, however, the only difference would be the price announced by, in this case, Chinese tire manufacturers. If the US could force Chinese tire manufacturers to pay the tariff themselves, they would simply raise the price of their tires on their websites. The new list price would be identical to the price American consumers paid under the current system, where Chinese manufacturers announced a lower price and then left the calculating and taxing to the US Customs and Border Protection agency. In the end, there would be no difference whatsoever to the American consumer.

The idea of External Revenue Service deserves credit for rhetorical flair. It is indeed a very clever turn of phrase. However, it remains a solution in search of a problem.